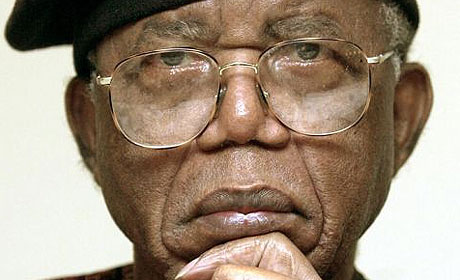

In my third year of graduate school at the University of Massachusetts, I had the good fortune to take a course in the "African Novel" given by one of its greatest practitioners--Chinua Achebe. That year, 1975, Achebe was invited to give a talk on African writing, during which he memorably denounced Joseph Conrad as a "bloody racist." Several of the assembled English professors, inclined as they were to see the study of literature as divorced from politics, were incensed at the effrontery of the remarks made by the regal and charismatic Achebe--after all, Conrad was a sacrosanct figure, unassailable, certainly beyond criticism by an invited (African) guest. [The text of Achebe's notorious talk is now included in the Norton edition of Heart of Darkness. So it goes.]

In my third year of graduate school at the University of Massachusetts, I had the good fortune to take a course in the "African Novel" given by one of its greatest practitioners--Chinua Achebe. That year, 1975, Achebe was invited to give a talk on African writing, during which he memorably denounced Joseph Conrad as a "bloody racist." Several of the assembled English professors, inclined as they were to see the study of literature as divorced from politics, were incensed at the effrontery of the remarks made by the regal and charismatic Achebe--after all, Conrad was a sacrosanct figure, unassailable, certainly beyond criticism by an invited (African) guest. [The text of Achebe's notorious talk is now included in the Norton edition of Heart of Darkness. So it goes.]It was under Achebe's guidance that I first read Alex la Guma, Dennis Brutus, Ayi Kwei Armah, Ngugi Wa Thiong'o, and Nuruddin Farah (nearly all of whom, from different nations, spent time in prison for their writing)--writers whose work was steeped in the realities of colonialism, racism, poverty, and violence. All at once my eyes were opened to another world; or, as I have since come to think of it, from that moment I ceased looking through a darkened glass and saw things, at last, in the clear light of day.

Alex la Guma's In the Fog of the Season's End, published in 1972, is a classic of anti-apartheid literature. La Guma spent years in prison before leaving South Africa for London in 1966.

"What the enemy himself has created, these will become battle-grounds, and what we see now is only the tip of an iceberg of resentment against an ignoble regime, the tortured victims of hatred and humiliation. And those who persist in hatred and humiliation must prepare. Let them prepare hard and fast--they do not have long to wait." (In the Fog...)

La Guma died in 1985, missing, tragically, and by just a few years, the historic moment, on February 2, 1990, when F.W. de Klerk, president of South Africa, announced that Nelson Mandela would be released from Robben Island after twenty-seven years--that moment was twenty-three years ago today. When Mandela walked away from Verster Prison on the eleventh of February the whole world watched, knowing that the end of the apartheid state in South Africa had come.

But not the end, surely, of South Africa's woes, including problems of race. It is a contemporary South African, Zakes Mda, who has taken up the story of black South Africa where La Guma and others* left off. The remarkably prolific Mda, (b. 1948) has examined the transitional period of South African history with a sensibility attuned to both the tragic and comic. In Ways of Dying, his first novel (published in 1995), an impoverished but resourceful Toloki invents a career for himself as a professional mourner--and the many funerals he attends (deaths through mischance and random violence are not uncommon in the townships) allow Mda to explore with compassion and pathos the plight of South Africa's poverty-stricken black majority. As I read Ways of Dying over the past couple of days, I was reminded again and again of a remarkable work of reportage I read late last year by Katherine Boo, Behind the Beautiful Forevers, a grim and strangely (sometimes) uplifting story of the lives of men and women and mostly children who live atop a vast sea of fetid garbage next to Mumbai's international airport. (The surprising sales of Boo's book cheered me a bit about the future of publishing, but not for long). As in Mda, Boo reveals, without editorializing, the desperate measures the poor must take to gain a foothold on the unwelcoming edges of modern "developing" nations. I thought again while reading Mda of how foolish it is to subscribe to theories of a "flat earth" or to believe in the glorious future of globalization. Instead of "false dawns" (John Gray's term for the delusions of modern capitalists) one reads Mda with a sense of wonder at the resourcefulness and pure spunk of people who have nothing--neither possessions nor hope. Toloki's memories of his home village allow Mda to evoke the traditional life of the townships, which is no better than life in the cities. And yet, gently, Mda allows his characters a glimmer of hope:

"Somehow the shack [in which Toloki has settled] seems to glow in the light of the moon, as if the plastic colours are fluorescent. Crickets and other insects of the night are attracted by the glow. They contribute their chirps to the general din of the settlement. Tyres are still burning. Tyres can burn for a very long time. The smell of burning rubber fills the air. But this time it is not mingled with the sickly stench of roasting human flesh. Just pure wholesome rubber."

Just pure wholesome rubber. Not much, but something.

The works of la Guma and most other African writers of note are available from Heinemann's The African Writers' Series--or at least they were. The series appears to have been discontinued, but many titles are available on-line (Heinemann appears to have been bought out by an educational publisher). Mda's books, or many of them, are readily available in attractive editions from Picador, a division of Farrar, Straus, and Giroux--http://www.picador.com/

*I have chosen to focus in this piece on two black South African writers; this is not to gainsay the power of the critique of South African society by its great "white" writers, J.M. Coetzee, Andre Brink, Nadine Gordimer, Breyten Breytenbach, and many others.

George Ovitt (2/2/13)

I was searching for the South African literature review and came across this post which is written quite well.

ReplyDeletesouth africa literature research review writing

Thanks for reading....go

ReplyDelete