Distant Lands: An Anthology of Poets Who Don't Exist

The idea of authorship should be unambiguous, and it mostly is--I am writing this, and such and such is my biography.

But let's look a little more deeply--Who wrote the Republic? Plato gets the credit, but was he merely recording the words of Socrates, or had he redacted his teacher's ideas to such an extent that they became his own? One might argue that Chaucer's Canterbury Tales--a tour de force of literary ventriloquism--is replete with heteronymatic (?) figures: Chaucer supplies each of his speakers with a full-fledged biography in the 'General Prologue', and then writes tales in the voice, and with a diction and tone appropriate to that character (think of the Nun's Priest and his tale, a perfect marriage of tale to teller). Or, sticking to the era of Chaucer for just a moment--who was William Langland, "author" of the great political poems collected as Piers Plowman? And what is the meaning of authorship in an age that valued plagiarism, that expected one author to copy the work of another?

Then there is the question of the pseudonym: are Dickens's Sketches by Boz (1836) an example of pseudonymous authorship, or was Boz a Dickensian heteronym? Was Józef Teodor Nałęcz Konrad Korzeniowski's decision to go with 'Joseph Conrad' the same sort of literary disguise as François-Marie Arouet's decision to become Voltaire? I can't imagine Voltaire as having any other name, but I can see Conrad in Konrad and might be able to make the Polish leap. Then what of Chloe Wofford or Neftali Ricardo Reyes Basoalto--can we imagine them as other than Toni Morrison and Pablo Neruda? Some pseudonyms seem almost an affectation--why Mark Twain when Sam Clemens was perfectly serviceable?--and others have a political or cultural purpose (George Eliot, or Howard O'Brien's sensible decision to become Anne Rice). So: names are complicated, and when writers change their names they do so for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is to deflect attention away from themselves and toward their books.

The melancholy Dane Søren Kierkegaard bridges the gap between pseudonymous authorship and fully realized herteronymic writing: Johannes de Silentio, "author" of Fear and Trembling, has a different style and tone than the "Victor Ermita" of Either/Or, but neither pseudonym is attached to a literary figure possessing a fully developed biography; indeed, Kierkegaard goes so far in his autobiographical writings as to discuss his use of pseudonymous figures in his literary productions, thus making the pseudonyms superfluous (rather like the way in which we are told that "Benjamin Black is the pen name of John Banville"--what's the point, aside from a possible tax dodge?).

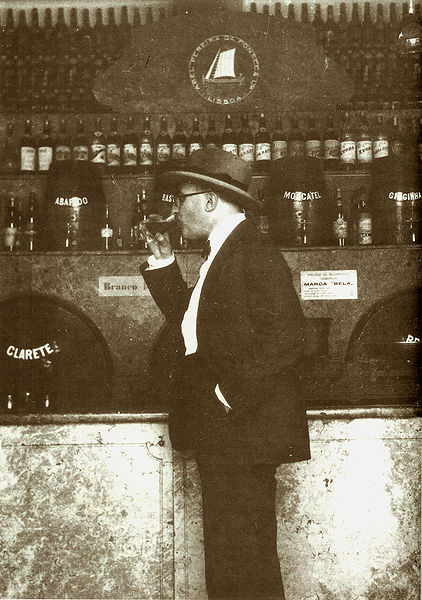

The greatest act of literary impersonation ever pulled off was Fernando Pessoa's, the man himself (I think) pictured here imbibing a bit of wine in his (and my) beloved Lisbon. Some attribute to Pessoa eighty full blown heteronyms, but this is an exaggeration--if a heteronym requires a biography, a variant style, and even a psychological profile (as with Bernardo Soares, author of The Book of Disquiet) then I'd credit Pessoa with having created no more than twenty (!) literary stand-ins. Pessoa wrote so much--with Proust, he is the greatest graphomaniac of the modernist era--that he needed to fob off some of his work on other selves, but, beyond the issue of overproduction requiring decentralization, the miracle of Pessoa's writing is that it appears that he became this roomful of other people.

The greatest act of literary impersonation ever pulled off was Fernando Pessoa's, the man himself (I think) pictured here imbibing a bit of wine in his (and my) beloved Lisbon. Some attribute to Pessoa eighty full blown heteronyms, but this is an exaggeration--if a heteronym requires a biography, a variant style, and even a psychological profile (as with Bernardo Soares, author of The Book of Disquiet) then I'd credit Pessoa with having created no more than twenty (!) literary stand-ins. Pessoa wrote so much--with Proust, he is the greatest graphomaniac of the modernist era--that he needed to fob off some of his work on other selves, but, beyond the issue of overproduction requiring decentralization, the miracle of Pessoa's writing is that it appears that he became this roomful of other people.

Which brings us, at long last, to the subject of this entry, the Polish poet and translator (from Italian to Polish) Agnieszka Kuciak. I made the acquaintance of Ms. Kuciak a few years ago through reading a handful of poems of hers in Six Polish Poets (ed. by Jacek Dehnel, Arc Books), but have since come into possession of her second book Distant Lands: An Anthology of Poets Who Don't Exist (her first was Retardacja [Retardation]) thanks to the good people at White Pine Press. Kuciak is a ventriloquist, a punner, a Pessoan creator of echoing voices--but she is also a delight straight up, as here:

The Lyric Poet Considers the Lake

Clean as the drowsy line of fate

is the lake's shoreline, the line of reeds and trees.

And just like in words where you discern the truth,

in water you can glimpse heaven's depths, cushioned

in clouds. It seems we can plummet there without fear,

and the fisherman with his pliant line and pole

is reeling in something from the absolute,

but he's on vacation: it doesn't interest him.

He'd prefer two kinds of carp: crucia and Common.

['reeling in something from the absolute,' a line I'd love to steal]

Then again, this little poem is signed by N. Miłosz, who is, we learn from the tongue in cheek (what's the Polish for this odd-ball idiom?) "Notes on Authors" is "A poet of amiable faith, known as the 'bishop of poetry.'" So, of course one thinks of Czeslaw at once--he who has "lyrically consecrated countless lakes and landscapes" and the joke is very good. Kuciak has created twenty-one voices--mini-heteronyms--and given each a part in the recitative that is Distant Lands. I don't know a word of Polish, but Karen Kovacik has done an admirable job of rendering the pitch and variation in this chorus of half-imagined voices ('half' because there is a continuo that clearly belongs to Kuciak, unmistakable in some poems, subtler in others). Thus we travel from the sonorous 'Nobody's' plosive "Fermeta"--"The Po glides by before me--with the paradox/and parasol that made me pause here in the lashing rain..." through Mrs. K's quotidian "On Losing My Third Pair of Sunglasses" with its kitchen images, through the mock serious resurrection rhymes of one "D.A.," which (wittily) quotes John Paul II thus: "His corpsely record has been meritorious, /Even the worms hold him in high regard/for how he's decomposed in the graveyard...." And so on...there's no buttoning this collection down or summing it up--the mimicry is quite fine, and non-stop.

Then again, this little poem is signed by N. Miłosz, who is, we learn from the tongue in cheek (what's the Polish for this odd-ball idiom?) "Notes on Authors" is "A poet of amiable faith, known as the 'bishop of poetry.'" So, of course one thinks of Czeslaw at once--he who has "lyrically consecrated countless lakes and landscapes" and the joke is very good. Kuciak has created twenty-one voices--mini-heteronyms--and given each a part in the recitative that is Distant Lands. I don't know a word of Polish, but Karen Kovacik has done an admirable job of rendering the pitch and variation in this chorus of half-imagined voices ('half' because there is a continuo that clearly belongs to Kuciak, unmistakable in some poems, subtler in others). Thus we travel from the sonorous 'Nobody's' plosive "Fermeta"--"The Po glides by before me--with the paradox/and parasol that made me pause here in the lashing rain..." through Mrs. K's quotidian "On Losing My Third Pair of Sunglasses" with its kitchen images, through the mock serious resurrection rhymes of one "D.A.," which (wittily) quotes John Paul II thus: "His corpsely record has been meritorious, /Even the worms hold him in high regard/for how he's decomposed in the graveyard...." And so on...there's no buttoning this collection down or summing it up--the mimicry is quite fine, and non-stop.

The delights are multiplied as the voices co-mingle, split, and play one against the other--the semi-serious, the burlesque, the lyrical, the lovely:

Vocation

She kneels by the bed's precipice,

and no one knows how she'll jump

over Egypt, over her own heart,

that place aching after him.

She could be faithful to the one who didn't touch her.

She could be faithful to the one who is gone.

She could be like the others, drinking wine,

desiring this body or that, untransformed.

She's more and more faithful

the less faith she has.

This one is signed by the great blind seer, Tiresias, "inwardly a woman himself."

Kuciak is an intelligent, witty, and skillful poet, and Distant Lands is a rich collection whose meditation on authorial identity--who is the poet? or, "all poets are liars"--added greatly to my enjoyment of a remarkably diverse and intellectually challenging volume.

Distant Lands is published by White Pine Press--http://www.whitepine.org/catalog.php

George Ovitt (2/27/13)

No comments:

Post a Comment