Bohumil Hrabal: Too Loud a Solitude

If you don't remember the 1953 novel Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury (I don't) you will most likely recall the 1966 film, directed by Francois Truffaut and starring Oskar Werner and Julie Christie. [Full disclosure: Jules et Jim, starring Oskar Werner, is not only my favorite film, but I am perhaps the only person who ever had an Oskar Werner poster in his college dorm room, until, that is, my roommate, who believed with mad fervency that Clint Eastwood was an actor, burned the poster to a cinder, claiming that OW was "too French."] Of course, in F 451Werner plays a fireman who, ironically, I suppose, burns books instead of dosing them with water (same dif) but later becomes one of the "book people" who memorize books to save them--though technically I suppose the memorized 'book' is only the content and not the book itself. Anyway, Werner selected the Tales of Edgar Allen Poe as his book to memorize, which would not have been my first choice, but that's neither here nor there. It wasn't a great movie, and Werner was much better in Ship of Fools, and sublime in Jules et Jim, but that too is off topic.

By the way, I suppose that if one were to remake Fahrenheit 451--and why not since every other B movie has been remade?--the star would be Jack Dorsey (ten points extra credit if you got this one), and instead of fire you'd have the kindle--get it?--and all the technophiles (instead of book people) would be dashing about reading ebooks and lecturing the world on how they're saving the forests.

Then again, when my copy of Bohumil Hrabal's Too Loud a Solitude arrived in the mail, the first thing I did was to open the book to the center and stick my nose right in the binding, just as if I were testing the waters with a Hess Cab. And after a deep sniff of the book I knew, without looking, it was A Harvest Book, published by Harcourt--it's easy really to tell--any book-mad person knows with his or her nose the difference between Harcourt,the old Vintage paperbacks, and the delightful aroma (of leather and parsnips) that told you a paperback was published by Doubleday-Anchor (defunct), or can identify the overpoweringly turpentine Dell Paperback scent, or, still my favorite, the hint of oak leaf and autumn-afternoon that came with every Modern Library Classic. [I just sniffed my Republic, purchased in 1964, and, sure enough, the oak fragrance is still there, forty-nine years later].

And what does your Kindle smell like?

So: books are tactile, physical objects, sensual pleasures, aromatic, hard (covers) and soft (pages), yellowing slowly like a fall season that hesitates to arrive, brittle as your mother's graying hair, the ink and paper and endpapers (marbled sometimes!), and those serrated Alfred A. Knopf edges that drop little bits of paper on your lap as you read--the loving way you take the new, stiff book and break it in, using your best pen and tidiest hand to inscribe (as I do) your name and the date you first held the book. For years I removed dust covers from hardbacks; now, when I can afford one, I keep it on, all the better to see it tear and crinkle.

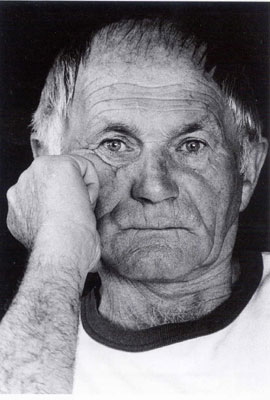

Now look at Hrabal's face. It is a lovely human countenance--worn and wrinkled and a little sad. The way a face might look if, for example, one has lived.

Too Loud: an idiot savant, or perhaps just an idiot, fond of beer, has spent thirty-five years pulping old books, and saving a few of them, storing them in his tiny room, a wall with two ton's worth of books, a wall of philosophy and history and ideas, some of which, at random, Haňtá, the pulp press operator, has memorized. And what does he do with the random ideas that have stuck in his head like the greasy remains of ruined books have stuck to his body?

What else would he do but weave what he has read into the fabric--however odd and eccentric--of his life? When he drinks, or makes love, or works, or thinks, he does so in a fog of ideas induced by the books he has saved from the pulper. Like anyone's mind, Haňtá's is untidy, but at least he can hang his random thoughts on the contents of the books he has read and memorized--Lao Tzu, Nietzsche, Holderline, and Hegel.

A friend of mine and I batted this idea back and forth: what happens if books become more real to us than life itself? Should we be upset if we if live vicariously, through the pages of the books we have come to love? I wonder sometimes why living through books should be different from any other kind of living--we live through our work, or other people, or some creed or ideology. Pure living--the thing itself--is hard to find. So why not through these little blocks of paper that put us--miraculously--inside the mind of someone else?

There they are, lined up like memory itself on the shelves, each one preserving a part of our life, associated with the people we knew then, the things we were thinking, the person we once were.

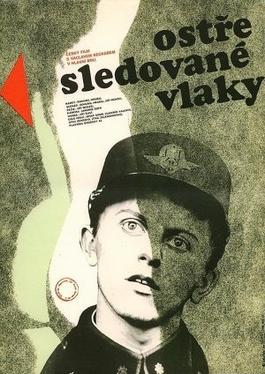

And who was this mysterious Czech writer? Most readers know him through the adaption of his Closely Watched Trains, which won an Oscar for Best Foreign Film in 1967. Hrabal was among the most popular Czech writers of the modern age. Born in 1914, his books have been translated into twenty-seven languages; like many other Czech writers whose books have political content (e.g. Milan Kundera), Hrabal was banned from publishing after the Prague Spring of 1968. My favorite of his books is Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age, a novel in one sentence (I'll write about it here sometime). But I loved the oddness of Too Loud a Solitude--it made me nostalgic for the great age of print, now, alas, passing from us. Hrabal died from a fall from a fifth story window in the Bulovka Hospital in Prague in February, 1997 at age 82.

Too Loud a Solitude was translated by Michael Henry Heim and is published by Harcourt.

A good brief introduction to Hrabal is found here: http://art-bin.com/art/ahrabaleng.html

George Ovitt (2/25/13)

No comments:

Post a Comment