A Walk with Robert Walser (1878-1956)

He loved to walk--he died in the snow on a stroll--was dapper, lonely (or not), wry and melancholy, Kafkaesque (though the influence ran the other way), intimate with the oddities of life, funny, and, in the end, perhaps, a little mad. "I am a little worn out, raddled, squashed, downtrodden, shot full of holes. Mortars have mortared me to bits. I am a little crumbly, decaying, yes, yes. That's what it does to you. That's life."("Nervous") Indeed life does just that: it wears you out. Walser is the great poet of fatigue, which is to say he does for ordinary life what urban intellectuals like Baudelaire or Benjamin did for ennui--he showed that fatigue is the human condition.

He loved to walk--he died in the snow on a stroll--was dapper, lonely (or not), wry and melancholy, Kafkaesque (though the influence ran the other way), intimate with the oddities of life, funny, and, in the end, perhaps, a little mad. "I am a little worn out, raddled, squashed, downtrodden, shot full of holes. Mortars have mortared me to bits. I am a little crumbly, decaying, yes, yes. That's what it does to you. That's life."("Nervous") Indeed life does just that: it wears you out. Walser is the great poet of fatigue, which is to say he does for ordinary life what urban intellectuals like Baudelaire or Benjamin did for ennui--he showed that fatigue is the human condition. In my favorite picture (he was often photographed, even in death), Walser resembles my father, who was himself a low-level clerk (Walser scrapped together a precarious living selling his writing; he moved often; lots of his stories deal with lodgings and landladies). "He goes for a walk. Why, he asks himself with a smile, why must it be he who has nothing to do, nothing to strike at, nothing to throw down?" ("Kleist in Thun") "With a smile," so the question is this: is he really asking, or is he affirming? That's the way it is with Walser's novels and especially with the short pieces--one can hardly call them stories: they are interludes--is our walker asking a question, inquiring into life, or does he know the answer already, does he know why he has "nothing to do" and wants merely to probe the dimensions of that "nothing"?

"As I looked on the earth and air and sky the melancholy unquestioning thought came to me that I was a poor prisoner between heaven and earth, that all men were miserably imprisoned in this way, that for all men there was only the one dark path into the other world, the path down into the pit, into the earth, that there was no other way into the other world than that which led through the grave."

In Walser, such somber reflections quickly give way to other feelings--often to self-mockery, or to affection for some undistinguished person, or to disdain for the pompous. Walser is flighty, his prose style rolls from formal diction and syntax--almost a parody of academic writing, stilted and dense--to breezy wit and heavy irony. The long story "The Walk" traipses through landscapes and moods suggestive not so much of Kafka as of Pessoa, as if Walser's narrator was reinventing himself in time with the slowly passing urban and rural scenery. If Walser were a wine, his label might direct the imbiber to search for overtones of Kafka and Klee (rectilinear miniatures going nowhere), of W.G. Sebald (wandering in blasted landscapes), and of the shape-shifting Pessoa, especially as encountered in the Book of Disquiet.

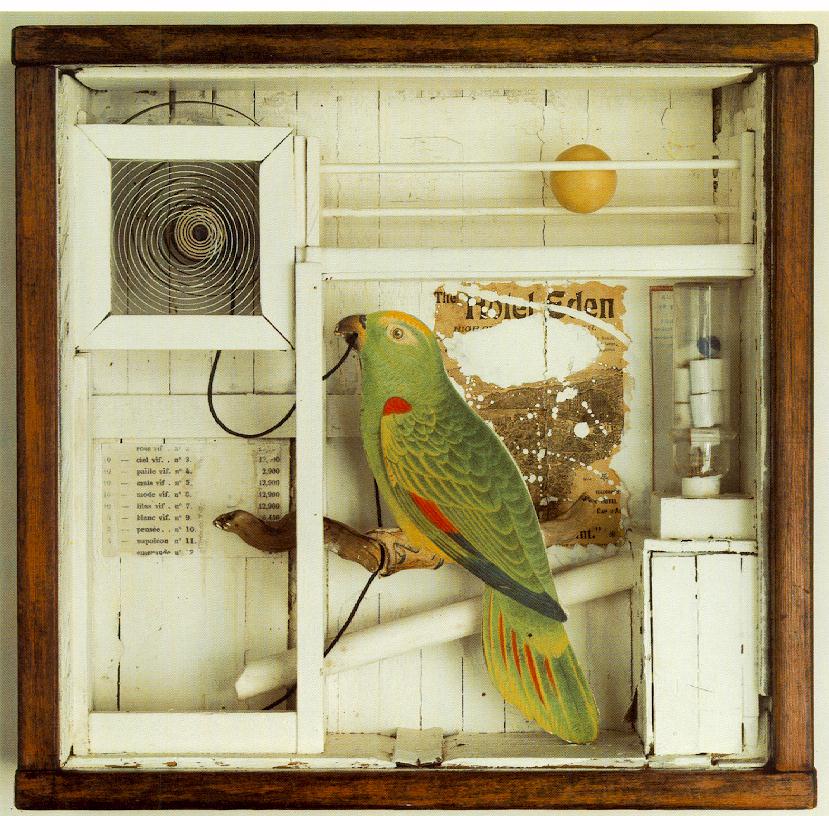

So long as we are playing this game--who does the writer remind me of?--my vote must be cast not for a writer at all, but for Joseph Cornell, the assembler of boxes, little collages cleverly done up from tattered bits of the discarded refuse of New York, cast off icons of modern life gathered together and assembled in Cornell's workroom on Utopia Parkway. Walser's small pieces of prose are like little boxes that assemble impressions, memories, nostalgia, and, as with Cornell, a sweet, unrepentant sadness almost never encountered any longer.

Untitled (The Hotel Eden)c. 1945 (140 Kb); Construction, 15 1/8 x 15 3/4 x 4 3/4 in; National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Walser was a graphomaniac--he lived to write, or perhaps he wrote to live. A selection of twenty-five of Walser's microscripts was published in 2010 by New Directions. Even after his hospitalization in 1933 at Waldau, Walser continued to write stories in a hand so tiny an entire text "could be written on the back of a business card." Appropriate, as the tiny German letters recreate worlds that are themselves miniatures of this world--"a clairvoyant of the small" was Sebald's judgment, and it is an incisive one.

But of course, as with Cabala, everything in the universe is contained in even one letter of the Secret Books. So it is with Walser. In his miniature studies of eccentrics ("Kienast was the name of a man who wanted nothing to do with anything"), oddities ("The Man With the Pumpkin Head"), and, of all things, trousers, Walser demonstrated that something can be said about nearly anything, and that, in the end, what is said amounts to nothing.

Robert Walser, Selected Stories, with an introduction by Susan Sontag, New York Reivew Books

J.M. Coetzee has written a fine essay on Walser, focused on two of Walser's novels, in the New York Review of Books.

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2000/nov/02/the-genius-of-robert-walser/?pagination=false

George Ovitt (2/21/13)

No comments:

Post a Comment