A Writer’s Notebook by Somerset

Maugham

Capri.

I wander about alone, forever asking myself the same questions: What is the

meaning of life? Has it any object or end? Is there such a thing as morality?

How ought one to conduct oneself in life? What guide is there? Is there one

road better than another? And a hundred more of the same sort. The other

afternoon I was scrambling among the rocks and boulders up the hill behind the

villa. Above me was the blue sky and all around the sea. Hazy in the distance

was Vesuvius. I remember the brown earth, the ragged olive trees, and here and

there a pine. And I stopped suddenly, in my confusion, my head buzzing with all

the thoughts that seethed in it. I could make nothing of it at all; it seemed

to me one big tangle. In desperation, I cried out: I can’t understand it. I

don’t know, I don’t know.

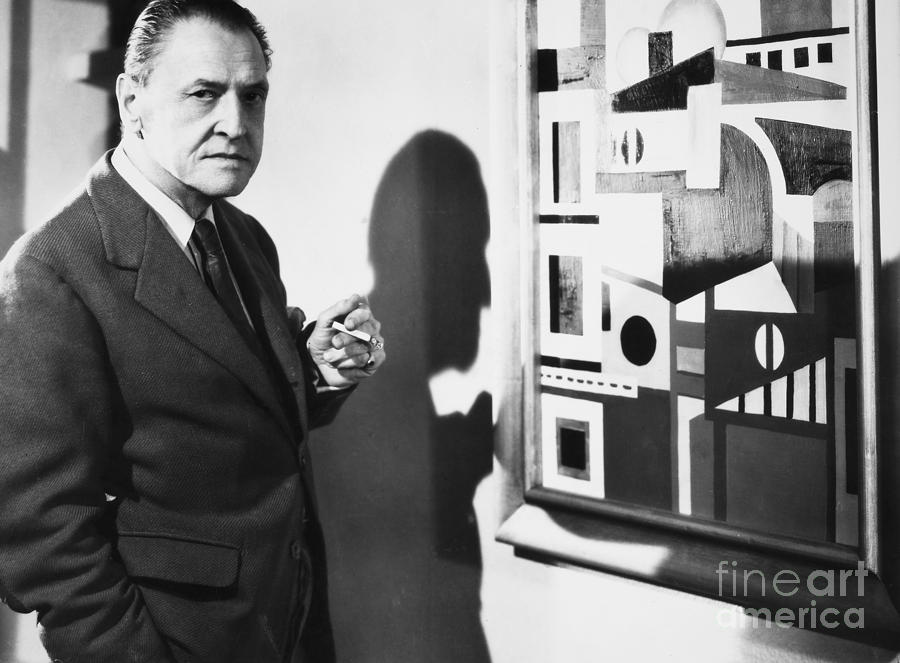

This entry from Somerset Maugham's A Writers

Notebook (1949) offers the reader a glimpse of the restless young author on

one of his many sojourns on the island of Capri, then (and now) a popular haven

for writers, artists, and homosexuals.

From 1892, when he was eighteen, until 1949, when this book was first

published, Maugham kept a notebook, diligently recording his thoughts and

observations, providing readers today with a fascinating journey into the life

and developing sensibility of this brilliant, decidedly private man. Author of such highly acclaimed novels as The Razor’s Edge, Of Human Bondage, Mrs.

Craddock, The Moon and Sixpence,

and Up at the Villa, as well as numerous

plays and short stories, including “Macintosh” and “Rain”, Maugham spent the

better part of his life travelling the world in search of experience and

understanding, both as a writer and man. His notebook, fragmentary as it is,

offers a compelling record of this.

Long a fan of Maugham’s work, I recently

discovered a copy of A

Writers Notebook among

my late step-father’s books. Remarkably,

I had never heard of it before and set down to read it at once. I was not disappointed. Varying from the philosophical to

the precocious to the lyrical, witty, mordant, and grave, the entries also vary

significantly in length, some of them a page or more in length, some – crisp as

aphorisms -- but a single sentence or two.

“Fragments of cloud, tortured and rent, fled across the sky like the

silent souls of anguish pursued by the vengeance of a jealous God,” reads one. “It goes hard with a

woman who fails to adapt herself to the prevalent masculine conception of her,”

reads another, while still another reads, “The hothouse beauties of Pater’s

style, oppressive with a perfume of tropical decay: a bunch of orchids in a

heated room.”

Traumatized when still a child by

the death of his parents, Maugham was a life-long introvert who stuttered terribly

when nervous, though his life was anything but reserved. Indeed he travelled widely, served as a spy

for Britain in both world wars, spoke many languages, was married, fathered a

daughter, achieved celebrity status among artists and writers, earned gobs of

money from his plays, and lived openly as a homosexual for extended periods of

time.

Maugham

died a dissolute man in 1967 in the south of France at the age of 91, “having

concluded he was not in the first rank of writers and, somewhat surprisingly,

that he had never had enough sex.” At least on the former point we can be the judge

of that.

Peter Adam Nash

No comments:

Post a Comment