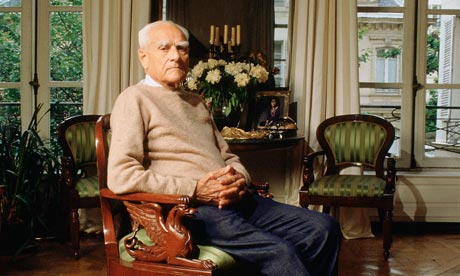

I like the writer as an older man, as here; the great Alberto Moravia, a writer who, above any other, evokes for me the urbane (and lost) life, as in La Dolce Vita, Marcello Mastroianni, Sophia Loren, and the trinity of twentieth century emotions--boredom, contempt, and amour (always problematic, often failed). Moravia's novels and stories, especially The Conformist (1947), Conjugal Love (1947), Contempt (1954), and Boredom (or The Empty Canvas 1960) are replete with the world-weariness and anxieties of a European post-war generation that lamented what was irrevocably lost--a generation that echoed the fin-de siecle sensibility of Joseph Roth, Stephan Zweig, and Robert Musil. In Moravia, the failure of love is the failure of larger hopes and a mirror for the duplicities of political and social life generally.

The three novellas collected in Two Friends, translated by Marina Harss, and beautifully produced by Other Press in a volume that also contains a splendid introduction by Thomas E. Peterson, variant textual readings of the novellas, and an account of the discovery of the typescript of the book in a suitcase in the basement of Moravia's home on Lungotevere della Vittoria, reprise Moravia's central themes: political turmoil, sexual longing, domestic betrayals, and bad consciences. For the admirer of Moravia, the great attraction of Two Friends is the opportunity to observe the writer's process of composition. Each of the three versions of the text contains essentially the same story--that of the troubled relationship between the wealthy playboy Maurizio and the idealistic/apathetic intellectual Sergio--but in each version Moravia shifted focus and narrative voice, struggling, it appears, to find the best way to tell the story.

In Version A, set in 1938, Maurizio and Sergio cope, each in his own way, with fascism and the war--Maurizio through womanizing and self-pity, Sergio through a kind of half-hearted anti-fascist engagement. In Version B, set in 1945, Sergio has joined the Communist Party, though not so much from conviction as from boredom; he is in love with Lalla, and, as he often does, Moravia demonstrates the ways in which a sexual relationship fails to compensate for a dearth of human feeling--in this case, Sergio's. Version C, narrated in first person by Sergio, is the most satisfying and fully realized of the three retellings of the story, with Sergio and Maurizio now plausible rivals in love and politics, and with a fuller development of Lalla's (now Nella) character.

Moravia's view of women can be odd--they at times appear to be nothing more than sexual vessels, or objects of male "ego-projection" (Moravia--the consummate Freudian novelist!), but, when he needed to do so, when the story required it, Moravia created women who were more fully realized characters than their often self-absorbed male counterparts. In my view, Moravia's strength lies in the ideas he puts at the center of his stories, those "what if" thought experiments that depend as much on mood and language and tone of voice as on plot or character.

Moravia is among the most cinematic of writers--that is perhaps why Bertolucci, Godard, de Sica, and others have made (quite good) films of his books. He crafts mise-en-scène like a screenwriter, then evokes character with precise exchanges of dialogue and minimal authorial interference.

Here is a bit of description, clear-eyed and rendered without nostalgia, taken from Version A. Sergio is seeing Maurizio's home and garden after many years away:

In [Sergio's] memory, the garden was large and full of trees; now it appeared to be a small rectangle with a few medium-sized trees and two or three flower beds surrounded by gravel paths. But the gravel was dirty and the flower beds had been invaded by weeds which had begun to turn yellow in the summer sun. The trees had grown wild, but no taller. He noticed an air of neglect and age, which he could not pinpoint in any single element but seemed to affect everything. Just as old age exacerbates certain characteristics, this air of neglect was neither poetic nor atmospheric; it was not the melancholy, charming neglect of an aging castle, but rather the casual indifference that clings to something that is neither beautiful or ornate.

Moravia's novels are available both from Other Press and New York Review Books. Here are the links:

http://www.otherpress.com/books and http://www.nybooks.com/books/

George Ovitt (1/21; Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Day)

No comments:

Post a Comment