Euphoria, by Lily King

Intertwined Lives: Margaret Mead, Ruth Benedict, and Their Circle, by Lois W. Banner

Steven Pinker's new book,

Enlightenment Now, argues that the world would be a better place if everyone followed the dictates of "reason"--defined, I suppose, as linear/empirical/analytical/Western thought. If, in PInker's view, everyone abandoned magical thinking, religion, superstition, and metaphysics the excesses of religious fundamentalism, irrationality, and cruelty would give way to material progress for all. Pinker, high atop Harvard Hill, reminds us that science and technology, leavened by the arts and humanities, have led to progress ever since the Enlightenment. E.O. Wilson, also at Harvard, has made the same point in a number of books, and corporate types like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates have found much to like in this rationalist view of progress. I remain unpersuaded. For one thing, "reason" is a form of problem solving; by itself, our rational (critical, analytical, scientific) mode of thinking has no material or moral content, as Kant famously understood. At best, "reason" functions as lines on a blank page, a rubric, an outline. Living a life, building a just society, includes not only analytical thinking but also willing, desiring, believing, and--let's face it--lots of luck.

***

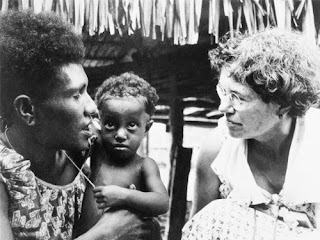

It is impossible, post-Freud, not to see the "primitive" peoples of Samoa as occupying a landscape of desire and will, of cultural expressions innocent of the Puritanical and patriarchal denial of the (female) body. No analytical reasoning was discovered by Mead and Benedict and Bateson and Boas in Samoa or the Amazon basin. The peoples of the Sepik River of New Guinea possess botanical knowledge one associates with hunter-gatherers, simple technologies (these are stone-age cultures), and an intimacy with nature that Rousseau would have admired. In her dual biography,

Intertwined Lives, Lois Banner does an admirable job of sketching the sexual repressions of American society in the early twentieth century and the effects of these repressions on the two most famous women anthropologists of the twentieth century. Havelock Ellis and other sexologists, bohemians, and free spirits defied the strictures on sexuality, but the psychic price paid by unmarried heterosexuals and all homosexuals (in the language of the age) was debilitating. In Samoa, where, in the 1930's, Christian missionaries were just beginning to spread the gospel of celibacy, a woman or a man could find a culture where sexual taboos were mild, where women had a measure of control over their reproductive lives, and where--best of all--no one was watching.

***

Of the many discouraging words I hear from young people, the most discouraging have to do with something that those of us brought up in the positivist tradition refer to as "human nature." Thus one can select any assumptions about human beings and ascribe them to "human nature." As in, "people are greedy; it's just human nature," or "people are violent; it's human nature." No amount of questioning can dislodge the conviction that all of us come hard-wired with precisely the set of innate characteristics that define twenty-first century American society--greed, materialism, indifference to other people, a fascination with violence (done to others), hedonism, and a vague understanding of the goods that comes from science and technology. I used to argue with people about "human nature," suggesting that even in purely Darwinian terms the "struggle for life" might as easily include altruism and self-sacrifice as greed and violence. But such arguments get nowhere. After all, the evidence appears overwhelming: nobody reports the countless daily acts of kindness and selflessness that make our families, communities, and our society workable. Those who are inclined to see the world as something other than a Hobbesian struggle are far less likely to boast about their beliefs. Ordinary men and decent women seldom go into public life, appear on television, or find themselves in the limelight. My students know of Gordon Gecko but have never heard of Dorothy Day.

***

I now respond to "everyone is greedy" with the simple admonition "read some anthropology."

***

Do you remember how moved you felt when you read Marjorie Shostak's

Nisa: The Life and Words of a !Kung San Woman? The book was a revelation, and while I have only taken one anthropology course in my life, Shostak, who died too young, got me to read more books like hers, first-person accounts of people whose world-view is wholly different from my own.

***

Rereading Ruth Benedict's

Patters of Culture in the light of Lily King's extraordinary novel

Euphoria, I am reminded again of the indelible fact that "human nature," like human culture, is as varied and rich as the heavenly constellations. I am fortunate enough to live in the same region as people for whom selflessness, community, collective identity, spirituality, and life mean more than greed, individualism, materialism, and death. If there is a single culture that practices selflessness and altruism than the "human nature" argument is fallacious. Marshall Sahlins's view of hunter-gatherers as the "original affluent society" and Marjorie Shostak's work on the !Kung open the door to our understanding of how so-called "primitive" societies give the lie to the notion that the apogee of human existence is found in the industrial West and in Enlightenment reason.

***

Lily King has taken the rudiments of the story of Margaret Mead, Gregory Bateson, and Reo Fortune in Samoa and turned it into a philosophical novel of the highest order. Nellie, Fen, and Bankson bring to their field work among the Tam three entirely different views of the purposes of anthropology, and, by extension, three different views of life. Nell is generous, open-minded, fearless, empathetic, warm, and humane. Fen is harsh and judgmental, engaged with other cultures to the extent that they allow him to ignore his own demons; he is married to Nell but treats her as if she were a foreign culture, someone whose habits of mind are unworthy of his attention. The effect that Fen has on Nell is predictable: she feels as if she is alone, a stranger in a (very) strange land, and while her isolation helps deepen her skills as a passive observer of other cultures, it diminishes her spirit. Bankson, who narrates most of the novel, is diffident, uncertain of his skills as a scientist, but, like Nell, he possesses patience and compassion. How ironic that in this novel it is the least "rational" among the scientists who understands most deeply what it means to live in a world defined by custom and not laws. Bankson's shy approach to his anthropological subjects takes him far more deeply into the world of the Tam than Fen's ultimately tragic attempt to

become his subjects. Lily King subtly brings Nell and Bankson together; that they will come to love one another is foreordained, but what's really beautiful is how the study of the Tam and the cautious circling of this trio of anthropologists reflect each other. Just as Nell and Bankson use their good hearts to uncover the mysteries of a stone-age culture, so too do they gradually begin to understand one another. Fen is the odd man out. He doesn't wish to study anything--he wants to dominate those around him, he wishes to exert his will over others, and in this he serves both as the perfect model of the Westerner among "savages" and the perfect foil to Nell and Bankson. The old dichotomy between head and heart is played out in

Euphoria with delicacy and brilliance.

***

The practice of field anthropology is an odd one. That a Westerner could "live among" people as foreign as the Tam (a fictional tribe, but there are plenty of real-life examples) and somehow come to "understand" them seems like folly. If the observation of a physical state changes that state and makes objectivity impossible, how much more so does the physical presence of a stranger among an isolated tribal group undo any possibility of understanding? And, worse, as

Euphoria makes plain, how much damage do well-meaning scientists do when they intrude upon the intimate lives of strangers?

Euphoria does many things well--it's a love story, an adventure novel, a philosophical investigation--but above all it is a book that raises fundamental questions about the pretensions of Western reason and science. Our brash conviction that we can understand, and by understanding control, the world feel especially hollow when that understanding and control is directed at a group of people who might prefer to be left in peace. The notion of "picking a tribe" and, uninvited, going to live among them, studying them as one might study an exotic species of bird, feels at times more like imperialism than science.

George Ovitt (16 May 2018)