My Year of Rest and Relaxation, Ottessa Moshfegh

The Journal, 1837-1861, Henry David Thoreau

The Intimate Merton: His Life from His Journals, ed. Patrick Hart and Jonathan Montaldo

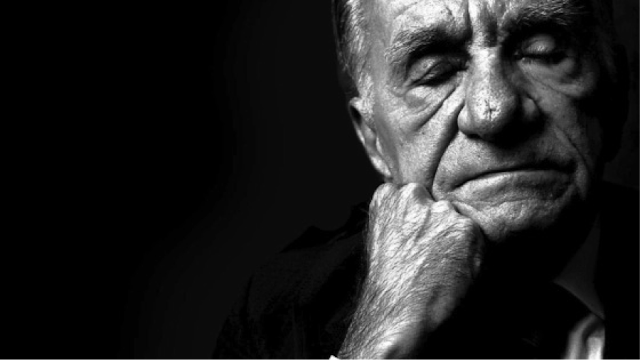

I've always been intrigued by solitude, by the rich resonance of being alone, and by those who can leave the world behind without a thought. Thomas Merton was such a person, and while his introspection, circling endlessly around his faults and his guilt before God, can become tedious, nonetheless his commitment to living an austere life of reading, writing, and meditation refreshes through its purity of purpose. Not only did Merton flee the life of an aspiring New York writer and intellectual for the austere existence of a Trappist monastery (a strict order requiring vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience), but at Gethsemane Abby, feeling distracted by his emerging fame as a writer, requested and was granted permission to live alone in the Hermitage (pictured here). His journals, of which The Intimate Merton is a selection, remind me of Thoreau's journals. Both men sought peace in solitude, both believed that separating themselves from "ordinary life" would put them in touch with higher truths, each had a "calling," and both were at times lonely and disappointed that in their solitude they found not fulfillment but a deeper, inchoate yearning. Being alone causes you to doubt yourself: perhaps that's why so few people are able to bear solitude.

"I sometimes seem to myself to owe all my little success, all for which men commend me, to my vices. I am perhaps more willful than others and make enormous sacrifices, even of others' happiness, it may be, to gain my ends. It would seem even as if nothing good could be accomplished without some vice to aid in it." Thoreau, Sept. 21, 1854

I find refreshing the minutiae of solitude, the little moments of unguarded confession that range from trivia--e.g. Thoreau's July 25, 1853 entry on the difficulty he has keeping his shoes tied--to the profound--Merton's tortured description of his (physical) love for the nurse he refers to as "M".

"I feel that somehow my sexuality has been made real and decent again after years of rather frantic suppression (for though I thought I had it all truly controlled, this was an illusion.) I feel less sick. I feel human."

Merton doesn't go so far as to break "the vow that prevents the last complete surrender," and he remains "suspicious of the tyranny of sex," but, taken together, his journal entries on his love for M show how difficult it is for even the most committed ascetic and solitary to give up life in the world.

***

Which is why, if you aren't a transcendentalist or a Trappist and you want to escape the world you have to go to sleep. Not for eight hours, but for eight months or a year or forever. You have to load up on Ambien and Restoril, Xanax and Ativan. Pay all of your bills automatically, quit your job, say goodbye to your (one) friend, and....go to bed.

It might not be fair to contrast the meditative and spiritual solitude of Thoreau with the seeming (see below) escapism of the narrator of Ottessa Moshfegh's latest novel My Year of Rest and Relaxation, but Moshfegh is so smart that the comparison is inescapable. Instead of turning a year of drug-induced "rest and relaxation" into a soap opera of millennial angst, Moshfegh imagines a young, pretty, well-off Upper-East-Sider as a kind of latter-day mendicant, one who seeks rebirth and reawakening with the same earnestness as a transcendentalist or Trappist. The young woman--who remains nameless throughout but tells her own story with an ingenuousness that is at the same time touching and creepy--retires to her couch, takes baskets of drugs prescribed by her lunatic psychiatrist, watches Whoopi Goldberg movies, and seeks not self-destruction but self-renewal, or maybe, in the jargon of today, a reboot. Her father has died of cancer; her mother has recently killed herself with pills and booze; her one and only friend is bulimic and deluded (the married man she loves will leave his wife for her someday); her on-and-off boyfriend is a sadist. Who wouldn't want to wake up from this nightmare?

Moshfegh writes scathingly of her own generation. Given the insincerity of so much contemporary writing, I find Moshfegh's deadpan style--bitterness unleavened by irony--refreshing. The narrator's cruel boyfriend Trevor is a dick, but in New York, on the cusp of Y2K, a beautiful young woman could do worse:

"[Trevor] was clean and fit and confident. I'd choose him a million times over the hipster nerds I'd see around town and at the gallery. In college, the art history department had been rife with that specific brand of young male. An 'alternative' to the mainstream frat boys and premed straight and narrow guys, these scholarly, charmless, intellectual brats dominated the more creative departments....'Dudes' reading Nietzsche on the subway, reading Proust, reading David Foster Wallace, jotting down their brilliant thoughts into the black Moleskine pocket notebook. Beer bellies and skinny legs, zip-up hoodies, navy blue peacoats, canvas tote bags, small hands, hairy knuckles, maybe a deer head tattooed across a flabby bicep. They rolled their own cigarettes, didn't brush their teeth enough, spent a hundred dollars a week on coffee."

When you get tired of "settling" for what is offered and unpalatable, you want nothing more--I feel the same way sometimes--than to sit alone, quietly, with a good book or a dumb movie. But Moshfegh isn't playing for cheap stakes--she never does, not in any of her stories or in her earlier novel Eileen (Stephan King meets Thomas Bernhard). Nothing less than a cleansing of her heroine's life, an erasure of memory, a recasting of the too, too solid flesh will do the trick, and so the young pretty woman who looks, we are told, like Kate Moss, sells all that she owns, hires a Japanese conceptual artist as a kind of caretaker, and leaves the world behind on a fake drug--Infermiterol, concocted in the manner of Don DeLillo's Dylar, a made-up magic bullet that eases one into three-day black outs, mini-deaths that, over the course of six months, succeed in erasing not so much memories as emotions about memories. It's a Trappist retreat; Thoreau's hikes on Cape Cod; May Sarton's winter alone in a Maine cabin; John Muir at Hetch Hechty, a Sand County Almanac for the lonely and neurotic urban dweller of our Brave New World.

Come to think of it, My Year of Rest and Relaxation, while wonderfully vulgar, is also, oddly, a religious book. Yes, to be born again we have to die, at least "symbolically," we have to take on a new body, a new self. Sleep, after all, is what Lazarus awoke from; death can't be provisional, so he was in a coma, or in REM sleep. He was not only awakened, but, we have to concede, renewed. How could it be otherwise? The great imperative of our age should be: WAKE UP! We're not just watching zombie movies these days; we're zombies ourselves. Not "the blind leading the blind," which at least is touching (think of those images from the trenches of WWI), but the mindless, the sleepwalkers, leading the sleepwalkers. So Moshfegh's heroine is Everywoman. As I read the book I kept thinking (at some level, not sure which one) not how shallow the narrator was, or how cowardly, but how brave. How estimable it was to say, "fuck it," and go to sleep. Not to become like everyone else, but to become someone else.

I won't say another word--the ending of the novel is beautiful and astonishing.

Yesterday, watching Stealth bombers and fighter jets zoom over my beloved city--not the Washington of Trump and the rest of the hoodlums, but the city of real people--I wished for some "Infermiterol," some "Dylar," for a long sleep, a week on the Concord and Merrimack, a retreat to a monastery, time alone to sort things out. To wake up once and for all.

George Ovitt, July 5th, 2019