Jerzy Andrzejewski, Ashes and Diamonds (1948)

As a historian, there are particular moments in European history that I especially want to understand; among them, preeminent even, is the passage of Eastern Europe from Nazi Occupation to Soviet-dominated governments. What events precipitated the defeat of nationalist aspirations in Poland (for example) during the critical years between the end of the war and the establishment of the Polish United Workers' Party under Boleslaw Bierut? The facts aren't difficult to come by; what is wanted is the feeling of these years, impressions of the primary participants in the nation's reluctant embrace of Stalinism, a sense of the human cost to a nation already dismantled by the Nazi Occupation, Hans Franks' systematic terror, and the extermination of Polish Jews. As usual, one must turn to works of literary art to gain insights, however limited, into the tragedy of post-war Poland.

Often the 'whys' of history are neglected in the standard textbooks. We might say, for example, that given the horrors of Nazism, the Soviet Union was a natural ally for Polish nationalists who survived the camps (non-Jewish Poles were sent to Arbeitslager or German slave labor camps like Gross-Rosen, which figures prominently in Ashes and Diamonds) and were liberated by the Red Army. But one suspects that this explanation is too simple; the truth, it would appear from Andrzejewski's brilliant and compelling novel, is that men and women were drawn into the sphere of Soviet influence, seduced by promises of brotherhood and Polish solidarity, for all sorts of reasons--out of patriotism, despair, personal ambition, greed, and idealism. Andrzejewski's remarkably well-drawn characters embrace or reject communism only in part because of their experiences in the war; a great strength of this novel is that it depicts the power of an individual's will even at the most "world historical" of moments.

|

| Barracks at Gross-Rosen

|

The deftness with which Andrzejewski sketches his characters is remarkable. During a briefing that will lead to the murder of a member of the Communist Party by a Polish nationalist, the Colonel, who has ordered the assassination, calms a young man's qualms by saying:

"We're living and fighting under very difficult and complex circumstances. But the war years, which were the testing years for everyone, have taught us that things have to be regarded in their elementary, basic set up. There's no time for subtle discrimination. If there had to be any discrimination, it must be simple and clear. Good is good, and evil evil. You agree?"

But of course nothing is ever so clear. For the socialist Podgorski, the world isn't divided into Manichean absolutes but gray with ethical questions and humane concerns; for the ambitious Mayor Swiecki the tragedy of Poland has served only to feed his ego--a mediocre man in peacetime, Swiecki remakes himself into the perfect Party toady, a yes-man for the cynical and brutal. For Kossecki, at one time a prisoner at Gross-Rosen, the aftermath of the war is fraught with fear and self-loathing for what he allowed himself to become in the camp. Opportunists like Drewnowski and Pieniazek (yes the names will give you fits!) have no allegiance to party or nation, while others, like the richly- drawn Communist Szczuka, have complex feelings about the meaning of commitment in the face of Poland's apocalypse (six million Poles, including over 90% of Polish Jews, perished in the war, out of a pre-war population of 35 million).

Among Andrzejewski's many narrative talents is the subtlety with which he moves his story forward. Much of the action of the book takes place in the Monopole, the central hotel and restaurant in the town of Ostrowiec, an establishment previously owned, we are offhandedly informed, "by Lewkowicz...one of the wealthiest men in Ostrowiec, [who] died with the rest of his family at Treblinka." Slomka, the new manager of the Hotel Monopole, has been the beneficiary of Nazi racial policies, but no further mention of this fact is made. In 1945 there is emerging a new order, a world that is a blank slate for the ambitions, idealism, and cruelty of every man and woman. When the new world (of communism or of Polish nationalism? That remains to be seen, at least in the novel) has been created, will it be "only ashes and confusion" or "a star-like diamond./The dawning of eternal victory?" [from the epigram by Cyrpian Norwid]. We know the answer of course--Poland's story since the war has been far more a tale of ashes than of diamonds. And Andrzejewski as well seems to have been fully aware of the historical situation of his country:

"The fact is I don't know what this new Poland is, just yet."

"How can I put it in a few words? It's difficult, that's probably the best way to describe the tangle of conflicts and contrasts which we're faced with at every step and which we certainly shan't resolve tomorrow or the day after. ...the war is over, but the fight here is only beginning."

Ashes and Diamonds was the third film in Andrzej Wajda's great trilogy which included A Generation (1954) and the unforgettable Kanal (1956) [Ashes and Diamonds appeared in 1958]. I saw the entire trilogy over one long, rather depressing weekend while in college. Andrzejewski wrote the screenplay for Ashes and Diamond; the films are available through Janus and provide an emotional immersion in both wartime and post-war Polish history.

Ashes and Diamonds, the novel, is brought to us by the wonderful folks at Northwestern University Press whose series of European Classics includes novels by Zweig, Arthur Schnitzler, Vladimir Voinovich, and the incomparable Heinrich Boll, who has written the introduction of Andrzejewski's novel.

http://www.nupress.northwestern.edu/Home/AllTitles/tabid/86/Default.aspx

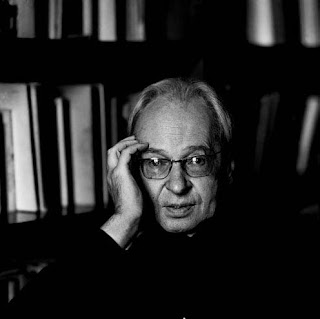

George Ovitt (4/16/13)