Go Tell It On The Mountain, and other works by James Baldwin

"I Am Not Your Negro," a film by Raoul Peck

"Black Body," Teju Cole

"James Baldwin's Istanbul," Suzy Hansen

David Leeming, James Baldwin: A Life

From Teju Cole we learn that James Baldwin, who struggled for eight years with the manuscript of his first novel, Go Tell It On The Mountain, finished the book at the chalet of Lucien Happersberger's family in the Swiss Alps, in the town of Leukerbad, in 1951. "From all available evidence no black man had ever set foot in this tiny Swiss village before I came," Baldwin wrote, and this sense of dispossession, of belonging no where because of the color of his skin, of being in possession of nothing but his black body--bereft of the Great Traditions of the (white) Western World--followed Baldwin throughout his life-long exile from America. In his essay on his stay in Leukerbad, "Stranger in the Village," Baldwin wrote:

"These people [the Swiss] cannot be, from the point of view of power, strangers anywhere in the world; they have made the modern world, in effect, even if they do not know it. The most illiterate among them is related, in a way that I am not, to Dante, Shakespeare, Michelangelo, Aeschylus, Da Vinci, Rembrandt, and Racine; the cathedral at Chartres says something to them which it cannot say to me, as indeed would New York's Empire State Building, should anyone here ever see it. Out of their hymns and dances come Beethoven and Bach. Go back a few centuries and they are in their full glory--but I am in Africa, watching the conquerors arrive."

Cole distances himself from Baldwin on this point: for Cole, the legacy of the the world's culture is his birthright as much as anyone's, but this, I'm afraid, is a matter of temperament and not a fact of history. All of Baldwin's writing, from the lyricism of Go Tell It On The Mountain to the realism and prophetic insights of Another Country, is a struggle against his conviction that "the American Negro has arrived at his identity by virtue of the absoluteness of his estrangement from his past." The sum total of Baldwin's novels and essays create a realistic--bitter yet truthful--version of the African-American past. Our fashionable cant about "inclusion" and our presumed belief in "diversity" wilt before Baldwin's decades-old but intensely relevant and clear-eyed view of the "Negro problem."

Baldwin's FBI file describes him as a person "likely to commit acts inimical to the interests of the United States," as a "person who has traveled abroad," and as someone who was rumored to be "an homosexual" at a time when the line between homosexuality and communism was thin indeed. The Klansmen who savagely beat and tortured and murdered African American men and women did not fall under the paranoid gaze of J. Edgar Hoover, but Baldwin and his friends seem all to have amassed hefty Bureau files.

Baldwin's FBI file describes him as a person "likely to commit acts inimical to the interests of the United States," as a "person who has traveled abroad," and as someone who was rumored to be "an homosexual" at a time when the line between homosexuality and communism was thin indeed. The Klansmen who savagely beat and tortured and murdered African American men and women did not fall under the paranoid gaze of J. Edgar Hoover, but Baldwin and his friends seem all to have amassed hefty Bureau files.In Raoul Peck's film, Baldwin speaks with quiet eloquence of the horrifying facts of American life: of white apathy, of moral bankruptcy, of the "death of the heart" that is manifest in the images of white power rallies from Birmingham, Alabama in 1963 to Ferguson, Missouri in 2014. Progress? To make the point that there's been none, director Peck overlays photographs of young African American's shot by the police in the last half-dozen years, lest we forget that our willingness to forget the past does nothing to erase it.

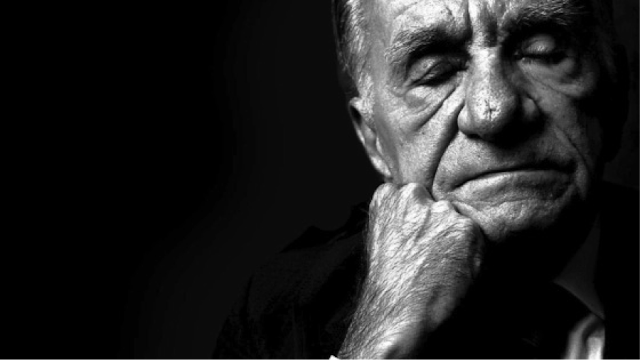

Baldwin's bitter words contrast with his gentle manner and with the luminous beauty of his prose. He was articulate even when he was incensed, and one feels the quiet despair that underlay everything that he wrote. His first novel, an autobiographical story that cut deeply into Baldwin's early life in Harlem, reads in parts like the King James Bible. John, Baldwin's fictional self, receives a few coins for his birthday (late in the day, nearly forgotten, in images that feel freshly lifted from "Araby"), and for the first time in his life goes to the movies, not daring to breath, "He stared at the darkness around him, and at the profiles that gradually emerged from this gloom, which was so like the gloom of Hell. He waited for the darkness to be shattered by the light of the second coming, for the ceiling to creak upward, revealing, for every eye to see, the chariots of fire on which descended a wrathful God and all the host of Heaven." So much of Baldwin's fiction is concerned with sin and redemption; he was willing to see himself as an imperfect being, a child of God, but shaped in large measure by a society that could only regard the color of his skin. In Baldwin's prose, from Go Tell It On the Mountain to If Beale Street Could Talk, one feels the weight of Baldwin's early fervor for the pulpit, his brief career as a street minister, a calling inspired by his stepfather.

In his novel Compass, the French writer Mathias Enard imagines Baldwin during the latter's long sojourn in Istanbul. Suzy Hansen writes, '“I feel free in Istanbul,” Baldwin told his friend, the Turkish writer Yaşar Kemal. “That’s because you’re American,” Kemal replied. Baldwin loved the city. He combed through the sahaflar, the second-hand bookshops that line the streets around the Grand Bazaar, their dusty wares stacked on haphazard tables. He sat by the New Mosque, drinking tea out of tulip-shaped cups, playing backgammon, and watching the fishermen’s wooden boats launch into the dirty waters of the Golden Horn.' Even more than Paris, the faded Turkish city was an escape from America's racism and cruelty, and "it was easier to be gay in Istanbul, easier to be black."

But it was never easy for Baldwin, no matter where he lived. While I admire David Leeming's biography of Baldwin--Leeming was a personal friend and had full access to Baldwin's papers--I wonder if Leeming makes too much of his subject's "search for his father" and not quite enough of the historical realities of America, in Harlem in particular, in the years leading up to World War II. Who can forget the prophetic jeremiad of The Fire Next Time, with its assertion that all of America's woes are attributable to white America's pathologies and not to any characteristic of the Negro:

"The white man's unadmitted--and apparently, to him, unspeakable--private fears and longings are projected onto the Negro. The only way he can be released from the Negro's tyrannical power over him is to consent, in effect, to become black himself, to become part of that suffering and dancing country that he now watches wistfully from the heights of his lonely power and, armed with spiritual traveler's checks, visits surreptitiously after dark."

This seems right: how often is this fear of blackness that is, in fact, a fear of an emptiness within our (white) selves a justification for cruelty based on an abject failure of human sympathy? "Therefore, a vast amount of the energy that goes into what we call the Negro problem is produced by the white man's profound desire not to be judged by those who are not white, not to be seen as he is, and at the same time a vast amount of the white anguish is rooted in the white man's equally profound need to be seen as he is, to be released from the tyranny of his mirror." We know from James McPherson's Why They Fought that Confederate soldiers, who were mostly dirt poor and despised by the planter elite for whom the Civil War was a fight, above all else, for the preservation of African chattel slavery, took up arms against the Union to defend their superiority to black men. And we know that even today, the shock troops of Klan and neo-Nazi racism are poor white men, themselves disenfranchised by corporate capitalism, who find in common cause in irrational hatred for a people with whom they have no contact. Fear of blackness was a brilliant insight, one that came to Baldwin during his years of exile, particularly in Istanbul where the color of his skin meant as little as it ever would.

My favorite scene in Peck's unforgettable documentary shows Baldwin standing in front of an audience, gesturing mildly, and explaining the ways in which his life has mirrored the lives of millions of African Americans. He turned this life, these lives, into enduring art and unforgettable polemic.

"Set thy house in order," the prophet Isaiah tells the King Hezekih, "for thou shalt die, and not live." And this message, that death comes for us all, and that it is in love and understanding that we make our peace with death, constitutes Baldwin's testimony in "Down From the Cross," written in 1962. "One is responsible to life," Baldwin wrote, "it is the small beacon in the terrifying darkness..."

George Ovitt (Presidents Day, 2019)