This morning my wife said to me, "This tea is perfect [she's Irish, so tea in the morning]; it's the perfect temperature; it's just strong enough, and I put in exactly the right amount of milk."

Late last night I fnished reading Tom McCarthy's remarkable novel Remainder, a book which is about the joy one has, or perhaps the madness one cultivates, in having things "just right." I hestitate to write anything about this novel as Zadie Smith has already written a brilliant review of it for the New York Review of Books [http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2008/nov/20/two-paths-for-the-novel/] but I disagree with Smith's argument that there are "two paths for the novel" and would like to say something about her views as well as a few things about Remainder. In her NYR piece, Smith argues that the novel might--from this moment--2008--on--take one of two diverging roads: the old worn out road of traditional realism, as in Joseph O'Neill's Netherland, or the fresh macadam of--what?--experiment, surrealism, anti-realism, as in McCarthy's Remainder. A great piece, bristling with ideas, references, provocations. Smith is about as good a reviewer as any, in a class surely with James Wood, but this time around I wondered if her assignment--reviewing, in tandam, Joseph O'Neill and Tom McCarthy--wasn't a set up for a concocted face off between two different approaches to fiction. Different, but not, in my view, incommensurable.

It seems to me that Smith offers a false dichotomy. She sets the two novels against one another in every way imaginable--the books are "one hundred eight degrees apart," but so are the authors (Oxford and Cambridge), and so, most of all, are the philosophical underpinnings of O'Neill's and McCarthy's fictional worlds. O'Neill retains the old, and apparently outmoded, faith in the existence of the self, that Cartesian "mirror of nature," an entity that can sniff out meaning in the events of everyday life or in the colloquies of the mind or in relationships or language. O'Neill's lovely book is fiction before Richard Rorty came along, before Derrida persuaded us that words aren't attached to anything, that selves are passe, or at least impossible to comprehend. Perhaps not worthy of comprehension, for what does the self tell us but that we yearn and are hopelessly inauthentic. Authenticity is the overriding concern of Smith's review--who has it and who doesn't--and I couldn't help but think as I read her perfect sentences that concern about 'authenticity' must be a New York-London-Paris intellectual thing--honestly, have you ever felt inauthentic? Do you even know what it would feel like to be inauthentic? I confess to being at a loss. Worrying about authenticity seems like the kind of thing Heidigger or Sartre might do, an existential concern with good faith, but nowadays, given the way the world turns, most of us worry more about making ends meet and finding time to read good books. So: that was my first problem with the 'two paths.'

McCarthy, in spare prose that is encrusted with irony--and by 'irony' I mean what Rorty means, which is the sense that no vocabulary is final, that words are attached to states of mind and of being only provisionally, and detach themselves promptly in the face of life's ceaseless contingencies--and disdains fixed meanings, a prose that abjures the traditional conventions of plot, character, theme, and voice for a philosophical reflection on the nature on happiness. Imagine what would happen if Slavoj Ziaek (heaven help us) were to write a novel. Things, unspecified, fall on the narrator's head; he is gravely injured, to the extent that he must learn all over how to perform life's simplest tasks (the description of relearning how to eat a carrot is brilliant and typical); the narrator is awarded a huge sum of money as compensation and is able to use this money to construst a repetitive, fanciful, banal, but utterly satisfying existence. I can't imagine how McCarthy would have constructed a 'pitch' for this book: Dear Mr. Sunny Metha: My novel is about a man who imagines a perfect life, one he has probably never lived, as consisting in smelling cooked liver and hearing a pianist flub passages from Rachmaninoff.....etc. No, one can see why it took seven years for this great novel to be published by a mainstream commercial publisher. The power of the book isn't in the 'story,' it lies instead in the tone, the absolutely affectless prose that is both funny and harrowing--yes, Kafka's Gregor Samsa comes to mind at once, and also Bernhard's endlessly circular sentences that play with theme and variation to the point of madness, and the cool, mad prose of some of David Foster Wallace's stories from Brief Interview With Hideous Men.

Anyway, Zadie Smith asks, in effect, which side are you on? Do you like O'Neill's mainsteamy but smart story of immigrants and cricket in New York post-9/11, or McCarthy's manifesto-like riffs on the nature of detachment and joy? And, in her intelligent review that almost persuaded me, Zadie found more to praise in McCarthy than in O'Neill--Remainder is, she thinks, the future of the novel. In fact, I note that one line of her review to this effect made it on to the front cover of the Vintage paperback of Remainder. So, Perhaps she is right.

Or is she? I find it difficult to make such a choice, or to find much validity the assumption that such a choice is required of readers. One might read both George Eliot and Kafka in the same day with equal, if different sorts of pleasure. O'Neill's novel, which I found engaging and thoughtful and well-written (and it led me to learn a lot more about cricket), didn't shake me up as McCarthy's did (I had dreams about Remainder, and I almost never dream about what I read) but my responses had nothing to do with the philosophy or future of fiction and everything to do with the fact that Remainder made different demands on me, demands that I was inclined to capitulate to and that were in accord with my frame of mind at the time I read it. Fictional meaning isn't Platonic, nor is it solely a function of the writer's intentions or of the novel's success in meeting them. Fiction's power and 'greatness' is contingent upon the reader. It is the reader who appears to be missing from Smith's account of the future of fiction. She writes on the novel as a writer, not as a reader, not as someone who would (as I do) hate the idea of narrowing the future of fiction to two possible 'paths.' Serious readers are, in my experience, promiscusous, requiring different forms of gratification at different times. O'Neill's realism, its respect for the conventions of the novel as a mirror of life, might be just the ticket on days when the ground shifts beneath our feet; on the other hand, McCarthy's odd-ball repetitions of events, his refusal to acknowledge normative rules of conduct or of expectation, his mordant wit, are qualities that might attract a reader who finds himself in a different frame of mind, perhaps more playful, maybe on vacation, or in love, or alone in Prague--who the hell knows?--in any case less attached to the bourgeois/realist conventions that Z. Smith professes to find confining (or does she? She did, after all, write a wonderful conventional realist novel--after E.M. Forester--On Beauty).

Is it absurd to point out that there is no such thing as "the novel"? That courses, articles, sections of bookstores, and blogs that purport to treat of the Novel are misleading--that books that call themselves 'novels' are as diversely constructed as human faces, variations on a theme that is as varieagated as life itself? This past, lucky week, I was able to read Remainder, Tabucchi's Requiem, Jo Ann Beard's In Zanesville, and Michael Connelly's new Harry Bosch mystery, Black Box. How could one begin to categorize these four diverse books using Smith's "whither the novel" framework? And each book was wholly satisfying--I loved reading Connelly late at night and then waking up to fifty pages of the smart young woman who narrates Beard's lovely book; and at lunch reading a dozen pages of Tabucchi's dream-like meditation on Portugal and Pessoa, and then late in the afternoon, after a walk, Tom McCarthy, CEO of the necronautrical society or some such. I don't want one flavor--I want them all. When it comes to books, I don't want two paths--I want them all.

George Ovitt

"He dreams of the day when the spell of the bestseller will be broken, making way for the reappearance of the talented reader, and for the terms of the moral contract between author and audience to be reconsidered." Enrique Vila-Matas

Monday, December 31, 2012

Thursday, December 27, 2012

William Matthews

Matthews (1942-1997) has been my favorite poet since a day in the early 90's, riding the train from DC to Philly, I happened to read--perhaps in the New York Review?--a poem of his called 'Snow Leopards at the Denver Zoo.' I don't think Matthews ever wrote a bad, or even an uninteresting, poem. Here's one for the end of the year, chosen from his Collected Poems. This one is, of all things, about the lost art of smoking. I read recently in the Times the view that the ban on indoor smoking had done as much as anything to kill off literary culture in New York City--an odd idea at first, then, not so odd at all. Here's to clean air, I suppose...note all the wonderful surprises here, so typical of Matthews....I put a link to this book, called Search Party: Collected Poems below.

Smoke Gets in Your Eyes

I love the smoky libidinal murmur

of a jazz crowd, and the smoke coiling

and lithely uncoiling like a choir

of vaporous cats. I like to slouch back

with that I'll-be-there-awhile tilt

and sip a little Scotch and listen,

keeping time and remembering the changes,

and now and then light up a cigarette.

It's the reverse of music: only a small

blue slur comes out--parody and rehearsal,

both, for giving up the ghost. There's a nostril-

billowing, sulphurous blossom from the match,

a dismissive waggle of the wrist,

and the match is out. What would I look like

in that thumb-sucking, torpid, eyes-glazed

and happy instant if I could snare myself

suddenly in a mirror, unprepared by vanity

for self-regard? I'd loose a cumulus of smoke,

like a speech balloon in the comic strips,

though I'd be talking mutely to myself,

and I'd look like I love the fuss of smoking:

hands like these, I should be dealing blackjack

for a living. And doesn't habit make us

predictable to ourselves? The stubs pile up

and ashes drift against the ashtray rims

like snow against a snow fence. The boy

who held his breath until he turned blue

has caught a writhing wisp of time itself

in his long-suffering lungs. It'll take years--

he'll tap his feet to music, check his watch

(you can't fire him; he quits), shun fatty foods--

but he'll have his revenge; he's killing time.

http://www.amazon.com/Search-Party-Collected-William-Matthews/dp/B000V5WM5U/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1356646094&sr=1-1&keywords=search+party+collected+poems

Smoke Gets in Your Eyes

I love the smoky libidinal murmur

of a jazz crowd, and the smoke coiling

and lithely uncoiling like a choir

of vaporous cats. I like to slouch back

with that I'll-be-there-awhile tilt

and sip a little Scotch and listen,

keeping time and remembering the changes,

and now and then light up a cigarette.

It's the reverse of music: only a small

blue slur comes out--parody and rehearsal,

both, for giving up the ghost. There's a nostril-

billowing, sulphurous blossom from the match,

a dismissive waggle of the wrist,

and the match is out. What would I look like

in that thumb-sucking, torpid, eyes-glazed

and happy instant if I could snare myself

suddenly in a mirror, unprepared by vanity

for self-regard? I'd loose a cumulus of smoke,

like a speech balloon in the comic strips,

though I'd be talking mutely to myself,

and I'd look like I love the fuss of smoking:

hands like these, I should be dealing blackjack

for a living. And doesn't habit make us

predictable to ourselves? The stubs pile up

and ashes drift against the ashtray rims

like snow against a snow fence. The boy

who held his breath until he turned blue

has caught a writhing wisp of time itself

in his long-suffering lungs. It'll take years--

he'll tap his feet to music, check his watch

(you can't fire him; he quits), shun fatty foods--

but he'll have his revenge; he's killing time.

http://www.amazon.com/Search-Party-Collected-William-Matthews/dp/B000V5WM5U/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1356646094&sr=1-1&keywords=search+party+collected+poems

Wednesday, December 26, 2012

Antonio Tabucchi: "But I have in me all the dreams of the world"

I was fortunate to come upon the novels of Antonio Tabucchi during this past year. I read Pereira Declares first, a book I happened to find in, of all places, the library of the school where I teach. I then read Little Misunderstandings of No Importance, and, the other day, Requiem: A Hallucination. I have been told by various people that if one wishes to make a living as a writer, one should write genre fiction--detective novels for example, or, I suppose, books about vampires and/or zombies. When I find myself (always unwillingly) in this conversation, which happens rather often, I always nod and say 'yes, of course,' but think, all the while, about writers like Tabucchi, writers so far out of the mainstream, so unfashionable, so inscrutable and idiosyncratic as to be the antithesis of the commercial--and therefore the writers whom I most admire. Tabucchi is the sort of writer Samuel Riba might have taken to Dublin to mourn the death of literary fiction; surely Tabucchi is among the writers least likely to survive an age in which self-styled 'educated' people download a single page of Anna Karenina or of Proust each day, avoiding, that way, any loss of contact with the myriad of other down loadable factoids of contemporary life. Books are, after all, just another commodity in a fully commodified world...

Tabucchi died this past year, on March 25th. He had many fine qualities as a writer and a person--he loved Portugal--he died in in Lisbon--and was enthralled by Pessoa, that demi-god of the obscure, and fado--the heartrending poetic songs that define Portuguese melancholy. Tabucchi stood for artistic freedom and the centrality of literature to our understanding of human experience. I am lucky to have many more of his books to read, though I will have to learn Italian to read some of them--much of his work remains untranslated, though the good people at New Directions (how would we live without them?) are doing their best. And if I do manage to learn Italian, I will be following Tabucchi's own example as he learned Portuguese to read Pessoa.

Requiem: A Hallucination is a slender volume that can be read in an afternoon. Like many other resolutely anti-popular writers, Tabucchi eschewed plots--those realist devices for turning novels into mirrors of nature--and focused instead on the kind of fleeting encounters that characterize our lives now. Tabucchi's life changed when he read Pessoa; he became, as it were, another of the great Portuguese poet's heteronyms, another voice for Pessoa, and in Requiem the narrator, who is surely Tabucchi himself, meets his master, the Guest, Pessoa himself:

You don't need me, I said, don't talk nonsense, the whole world admires you, I was the one who needed you, but now it's time to stop, that's all. Did my company displease you? he asked. No, I said, it was very important, but it troubled me, let's just say that you had a disquieting effect on me. I know, he said, with me it always finishes that way, but don't you think that's precisely what literature should do, be disquieting I mean, personally I don't trust literature that soothes people's consciences.

It takes a minute to sort out the pronouns in this piece of dialogue; Tabucchi conflates his voice with Pessoa's; they become one voice: 'I don't trust literature that soothes people's consciences.' Pessoa's genius lay in the channeling of the voices of those who have looked inward for meaning. No one trusts the poet for guidance; but if the poet is a bookkeeper, or if the poet is a businessman, or an Everyman--and if the truths we need to hear and to dream are configured in a multitude of ways by a multitude of voices--then we might just listen. Tabucchi follows Pessoa in creating different voices--waiters and cabdrivers and cemetery keepers and a fortune-teller and Pessoa himself--charging each with uttering a fragment of the truth that obsessed both Pessoa and Tabucchi, a truth described by the Portuguese word saudade: the sense of nostalgia we all feel for lost things, for people and places, for the past. Most great books express this truth--think of Proust--and were written by those who wished to preserve not only the events of the past, but the notion--so out of date today--that the preservation of memory is itself central to being human. Pessoa is the poet of loss; Tabucchi's Requiem mourns the loss of the Poet. At the end of the novel the Guest, Pessoa, simply vanishes, and the narrator can only wonder what it is he is saying goodbye to...

Tabucchi has arranged it so that we say goodbye to everything in Requiem: to time and to literature and to those who have inspired us. When, years ago, my wife and I sat in a bar in Lisbon's Old City listening to 'Esmeralda Maria' singing of her dead lovers, I thought at once of the great blues artists whose music has sustained me over the years--to recordings of Billie Holiday or Sarah Vaughn or Nina Simone--and to the sense that the blues isn't about mourning the loss of a feckless lover but the mourning induced by loss itself--fado has no specific object, nor does saudade. The point of fado, of the blues, of Requiem, is the feeling of having missed something--but what? The clearest literary exposition of this feeling lies in 'Combray', those first, inimitable pages of Swann's Way, still, after forty years, my touchstone for the expression of beauty in art.

Pessoa is the great poet of renunciation; Tabucchi pays tribute to Pessoa in Requiem, a book that goes perfectly with Vila-Matas's Dublinesque, the inspiriation (see below) for these informal meditations on books and reading.

See http://www.eclectica.org/v9n4/gray.html for a nice overview of Tabucchi's work...

George Ovitt

Tabucchi died this past year, on March 25th. He had many fine qualities as a writer and a person--he loved Portugal--he died in in Lisbon--and was enthralled by Pessoa, that demi-god of the obscure, and fado--the heartrending poetic songs that define Portuguese melancholy. Tabucchi stood for artistic freedom and the centrality of literature to our understanding of human experience. I am lucky to have many more of his books to read, though I will have to learn Italian to read some of them--much of his work remains untranslated, though the good people at New Directions (how would we live without them?) are doing their best. And if I do manage to learn Italian, I will be following Tabucchi's own example as he learned Portuguese to read Pessoa.

Requiem: A Hallucination is a slender volume that can be read in an afternoon. Like many other resolutely anti-popular writers, Tabucchi eschewed plots--those realist devices for turning novels into mirrors of nature--and focused instead on the kind of fleeting encounters that characterize our lives now. Tabucchi's life changed when he read Pessoa; he became, as it were, another of the great Portuguese poet's heteronyms, another voice for Pessoa, and in Requiem the narrator, who is surely Tabucchi himself, meets his master, the Guest, Pessoa himself:

You don't need me, I said, don't talk nonsense, the whole world admires you, I was the one who needed you, but now it's time to stop, that's all. Did my company displease you? he asked. No, I said, it was very important, but it troubled me, let's just say that you had a disquieting effect on me. I know, he said, with me it always finishes that way, but don't you think that's precisely what literature should do, be disquieting I mean, personally I don't trust literature that soothes people's consciences.

It takes a minute to sort out the pronouns in this piece of dialogue; Tabucchi conflates his voice with Pessoa's; they become one voice: 'I don't trust literature that soothes people's consciences.' Pessoa's genius lay in the channeling of the voices of those who have looked inward for meaning. No one trusts the poet for guidance; but if the poet is a bookkeeper, or if the poet is a businessman, or an Everyman--and if the truths we need to hear and to dream are configured in a multitude of ways by a multitude of voices--then we might just listen. Tabucchi follows Pessoa in creating different voices--waiters and cabdrivers and cemetery keepers and a fortune-teller and Pessoa himself--charging each with uttering a fragment of the truth that obsessed both Pessoa and Tabucchi, a truth described by the Portuguese word saudade: the sense of nostalgia we all feel for lost things, for people and places, for the past. Most great books express this truth--think of Proust--and were written by those who wished to preserve not only the events of the past, but the notion--so out of date today--that the preservation of memory is itself central to being human. Pessoa is the poet of loss; Tabucchi's Requiem mourns the loss of the Poet. At the end of the novel the Guest, Pessoa, simply vanishes, and the narrator can only wonder what it is he is saying goodbye to...

Tabucchi has arranged it so that we say goodbye to everything in Requiem: to time and to literature and to those who have inspired us. When, years ago, my wife and I sat in a bar in Lisbon's Old City listening to 'Esmeralda Maria' singing of her dead lovers, I thought at once of the great blues artists whose music has sustained me over the years--to recordings of Billie Holiday or Sarah Vaughn or Nina Simone--and to the sense that the blues isn't about mourning the loss of a feckless lover but the mourning induced by loss itself--fado has no specific object, nor does saudade. The point of fado, of the blues, of Requiem, is the feeling of having missed something--but what? The clearest literary exposition of this feeling lies in 'Combray', those first, inimitable pages of Swann's Way, still, after forty years, my touchstone for the expression of beauty in art.

Pessoa is the great poet of renunciation; Tabucchi pays tribute to Pessoa in Requiem, a book that goes perfectly with Vila-Matas's Dublinesque, the inspiriation (see below) for these informal meditations on books and reading.

See http://www.eclectica.org/v9n4/gray.html for a nice overview of Tabucchi's work...

George Ovitt

Monday, December 24, 2012

Christmas Eve: Wallace Stevens

Elvis is singing 'Blue Christmas' in the living room..my children are dreaming (awake!) of sugar plums upstairs, and I am reading Harmonium. I have always loved this piece of it: "....who listens in the snow,/And, nothing himself...." The casual "nothing himself" is brilliant. Is there a better poem in the American literary tradition?

Merry Christmas.

The Snow Man

One must have a mind of winter

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;

And have been cold a long time

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitter

Of the January sun; and not to think

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,

Which is the sound of the land

Full of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare place

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

Merry Christmas.

The Snow Man

One must have a mind of winter

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;

And have been cold a long time

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitter

Of the January sun; and not to think

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,

Which is the sound of the land

Full of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare place

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

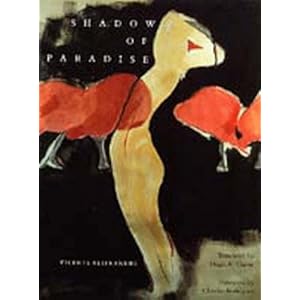

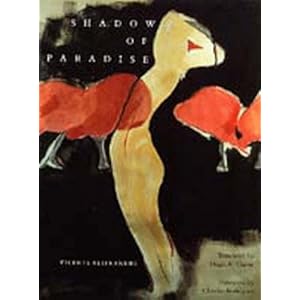

Shadows of Paradise, Vicente Aleixandre

Aleixandre, Nobel laureate in 1977, was a prolific poet, if relatively unknown in North America. I came across a bilingual selection of his work in a Philadelphia bookstore in 1980, A Longing for the Light, and was struck by the lyrical beauty of his Spanish. Shadows of Paradise, translated in the late '70's, is still in print, and I have been savoring the collection since being given a copy two months ago. Shadows of Paradise was composed during World War II and published in 1944--the sense of loss and longing that pervades the poems, the classical and austere style, and the melancholy of Aleixandre's voice seem appropriate both to that age and to our own:

Confundes ese mar silencioso que adoro

con la espuma instantanea del viento entre los arboles.

Pero el mar es distinto.

No es viento, no es su imagen.

No es el resplandor de un beso pasajero,

ni es siquiera el gemido de unas alas brillantes.

Aleixandre has been fortunate in his translators. Hugh A. Harter, who rendered Shadows of Paradise faithfully into sad cadences that unfold, poem by poem, to the lachrymose "Final Love," doesn't have to do much with Aleixandre's lovely lines:

Let the world spin on, and give me,

give me your love, and let me in futile

knowledge die, as kissing you we wheel

through space, and a star ascends.

Reading through this collection--and it's best to read Shadows as an unfolding lyric narrative rather than as individual poems thematically related--I thought of Antonio Machado's Fields of Castilla (1906-1917), also evocative of a lost age, also wistful and intimately connected both to Spain's history and its earth: "No todo/se lo ha tragado la tierra." But then again, most things are.

http://www.amazon.com/Shadow-Paradise-Vicente-Aleixandre/dp/0520082575/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1356378151&sr=1-1&keywords=shadows+of+paradise

http://www.amazon.com/Shadow-Paradise-Vicente-Aleixandre/dp/0520082575/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1356378151&sr=1-1&keywords=shadows+of+paradise

Confundes ese mar silencioso que adoro

con la espuma instantanea del viento entre los arboles.

Pero el mar es distinto.

No es viento, no es su imagen.

No es el resplandor de un beso pasajero,

ni es siquiera el gemido de unas alas brillantes.

Aleixandre has been fortunate in his translators. Hugh A. Harter, who rendered Shadows of Paradise faithfully into sad cadences that unfold, poem by poem, to the lachrymose "Final Love," doesn't have to do much with Aleixandre's lovely lines:

Let the world spin on, and give me,

give me your love, and let me in futile

knowledge die, as kissing you we wheel

through space, and a star ascends.

Reading through this collection--and it's best to read Shadows as an unfolding lyric narrative rather than as individual poems thematically related--I thought of Antonio Machado's Fields of Castilla (1906-1917), also evocative of a lost age, also wistful and intimately connected both to Spain's history and its earth: "No todo/se lo ha tragado la tierra." But then again, most things are.

http://www.amazon.com/Shadow-Paradise-Vicente-Aleixandre/dp/0520082575/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1356378151&sr=1-1&keywords=shadows+of+paradise

http://www.amazon.com/Shadow-Paradise-Vicente-Aleixandre/dp/0520082575/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1356378151&sr=1-1&keywords=shadows+of+paradiseSunday, December 23, 2012

Ben Lerner: Leaving the Atocha Station

Ben Lerner definitely looks like someone with whom a talented reader--hell, any serious reader--would enjoy having a beer. Or a spliff. I admit I had to look this word up when I first encountered it in Lerner's fine first novel, Leaving the Atocha Station. The hero of LAS, Adam Gordon, is fond of pot, lying, women who dislike him, poetry, and, mostly, himself. I did a double-take at Adam Gordon--at first I was looking for a palindrome, 'no drug ma' maybe--but then I got the joke, which I think is Adam's All-American credentials, his heartland upbringing, his education at Brown, his vague links to the New York literary scene--Lerner's strange narrator is designed to be a sort of Everyman and a nobody at the same time. I thought of the poet Bolano (that's an invisible tilda over the 'n') pre-Savage Detectives, working at odd jobs and writing furiously, or of poets and writers I've known whose apparent blandness mask a fabulist's heart. And Adam is a fabulist. The two strongest riffs in the novel are that Adam is incapable of telling the truth and that Adam isn't ever sure, when he is speaking (in Spanish), that he is saying what he wishes to say. I suspect Lerner has read Wittgenstein and recognizes the way the language game is faught with ambiguities that shift the ground of meaning from under us. Lerner is very smart in the way he uses these two ideas to create a kind of anti-Jamesian American--a not-so-innocent abroad. At a poetry reading, Gordon hears his own poetry, translated into Spanish by a friend:

At first I heard only so many Spanish words, but nothing I could recognize as my own; after all, there was nothing particularly original about my original poems, comprised as they were of mistranslations intermixed with repurposed fragments from deleted e-mails. But as the poem went on I slowly began to recognize something like my voice, if that's the word, a recognition made all the more strange in that I'd never recognized my voice before. Something in the arrangement of the lines, not the words themselves or what they denoted, indicated a ghostly presence behind the Spanish, and that presence was my own, or maybe it was my absence; it was like walking into a room where I was sure I'd never been, but seeing in the furniture or roaches in the ashtray or the coffee cup on the window ledge beside the shower signs that I had only recently left.

This passage, and the larger scene of which it is a part, clarify the attractions of this book: generally when we are confronted with a story about an 'undeveloped' character we can count on two things: that the character will be in some sense admirable or an embodiment of qualities whose revelation is uplifting for the reader--this formula is relentlessly deployed by bestselling authors; the other certainty is that Adam Gordon will come into possession of some insight that will 'resolve' the ambiguities of this short novel--ambiguities of language, motivation, ethical principles, aesthetic viewpoints, you name it.

Well, not here.

Adam Gordon remains a laconic, mendacious, rather unctuous fellow, a phony who appears brilliant because he knows when to keep his mouth shut, who seems worthy of affection because he shrouds himself in myth, brilliant because, like many an American go-getter, he is consummately disingenuous. In a brilliant scene at the end of the novel, Lerner puts Gordon on stage with a group of academics and experts to comment on 'literature now.' In a marvelous deployment of dry wit (I did not, I have to say, find LAS 'funny' or 'very funny' as two of my favorite critics [Lorin Stein and James Wood] did; however, de gustibus applies especially to wit), Lerner has Gordon memorize a few banalities in Spanish that he can deploy as needed. Of course, in such a setting, banalities are just what is needed, and Gordon comes off not as facile, but gnomic and very smart. Lerner nails this sort of faux-cultural circus perfectly.

Lerner writes prose the way poets write prose: "I reread Levin's most soul-wrenching scenes without the slightest affective fluctuation'" Gordon's "reading" of Tolstoy is a kind of shtick in LAS: one struggles to imagine what this fellow on a fellowship could find in the moralistic prose of the good Count, quintessential realist and enemy of irony. Gordon, for his part, is irony, from his posing as a poet, to his unaccountable yearning for two women who appear alternately to despise and desire him, to his impetuous self-creations (expensive meals and gifts used to deflect moments of personal crisis that pass like the effects of his white pills and, yes, his spliffs.)

So: you take some tobacco out of a cigarette and put in some pot. And my thought was along the lines of why ruin either a good cigarette or good joint?

Leaving the Atocha Station is a wonderful novel, beautifully written and dead on in its evocation of American phoniness. I'd ignore the cover blurbs--which are laudatory and universally, in my opinion, wrong about the book's many qualities.

Dublinesque

This blog takes its theme and contents from a passage in Dublinesque, by Enrique Vila-Matas. In the course of a morning full of melancholy ruminations about the sorry state of literary publishing, Vila-Matas has his narrator, Samuel Riba--who is, one suspects, Vila-Matas himself--offer the following reflection:

This blog takes its theme and contents from a passage in Dublinesque, by Enrique Vila-Matas. In the course of a morning full of melancholy ruminations about the sorry state of literary publishing, Vila-Matas has his narrator, Samuel Riba--who is, one suspects, Vila-Matas himself--offer the following reflection:

"He dreams of the day when the spell of the best-seller will be broken, making way for the reappearance of the talented reader, and for the terms of the moral contract between author and audience to be reconsidered. He dreams of the day when literary publishers can breathe again, those who live for an active reader, for a reader open enough to buy a book and allow a conscience radically different from his own to appear in his mind. He believes that if talent is demanded of a literary publisher or a writer, it must also be demanded of a reader." (page 51)

In this blog we propose to offer comments on literary fiction that does just this--that 'allows a conscience radically different from his own to appear'--to express our admiration for important works of literary fiction, books that are overlooked by most readers in the search for the newest, trendiest books offered in the pages on the New York Times or other mainstream outlets.

We are hardly alone in writing about literary fiction, and we will pay homage not only to books but to some of the many thoughtful and inspiring reviews that one finds in select corners of the web.

Neither Peter nor I are professional reviewers, professors of literature (or of anything else), or literary critics. We are serious lovers of literary fiction and poetry, who hope, someday, to be talented readers.

Thanks for reading.

George Ovitt and Peter Adam Nash